Pages

Saturday, December 17, 2022

Three Books That Broke the Reading Drought, Part 2

Sunday, November 6, 2022

Three Books That Broke the Reading Drought, Part 1

Wednesday, September 21, 2022

Art Imitates Art: Poetry Postcard Fest 2022 Wrap-Up

|

| Cards I got from other Festers. Go, Group 9! |

The annual August writing marathon is done—30 days, 31 poems written on 31 hand-painted postcards and mailed off to other poets and artists around the country (and one in the UK). This was my 10th year doing the August Poetry Postcard Fest, and as always, it was… different than other years. It’s different every time; it grows and morphs around what’s happening in the rest of my life, and in the world. This year, the writing came easy. I rarely was stuck for an idea, and I didn’t feel the usual peevish rebellion about having to write on a schedule, even though it was also a really busy month at work. Every few evenings I’d write three or four poems, and then I'd take a few days off. I like that pace with short postcard poems, which tend to ripen better in batches or something.

Serial and random

I started out the Fest bent on seriality. Weeks earlier, I knew exactly what I wanted to write about: I’d turned 60 a few months earlier, and it was weirding me out. I just could not believe I was 60. I know lots of people in their 60s who suddenly got hernias and prolapsed bladders and tumors. When I think of 60 I see washed-out gray, stooped, moving slowly. Possibly shaking a rolled-up newspaper at a kid riding a bike too fast. 60 has moved in like a houseguest I didn’t invite and will not leave. I guess I’ll have to make my peace with 60; in the meantime, I plan to kayak the hell out of it.

So the first few poems of the month were all about 60—puns and visual images of the number, free-associated strings of maladies and misery. But by about the fifth poem, I could feel that I wasn't making any peace with 60, and not even very much sense. I’m not sure any of those poems are keepers. So I moved on to other ideas.

After that there were a lot of random poems, experiments, some of which turned colors and boiled over, which is good, and some of which didn’t. Two of my favorites were about black widow spiders. I always seem to write about black widows during August, since they’re in the crooks and corners of patios and garages around here, growing big and shiny in the sweltering heat and knitting their cottony egg sacs. Of course their ferocity is legendary, but in reality they’re mostly timid and serene. I always get a lot of poetic mileage out of black widows.A game of 20 extras

This year I again hand-painted all of my postcards. I love that ritual, and I have to get an early start on it; I was painting the cards back in May or June so I could paint three or four at a time and then take a few days off (same as the writing). This year I used mostly Strathmore watercolor postcards; after experimenting last year, I settled on Strathmore as a good compromise between durability and quality. (Plus Strathmore used to have a mill in Westfield, Mass., where I lived, and they were a big employer there.) I also used a few scraps of cotton paper, always my favorite for watercolors, but cotton feels too pliable to send naked through the mail, so I popped those into envelopes so they wouldn’t get scuffed.

|

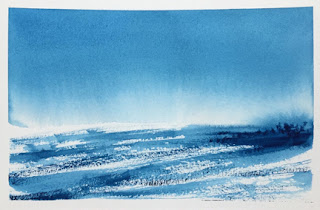

| A keeper. Can’t go wrong with Prussian Blue. |

Some of the paintings I especially liked this year were monochromes and duochromes, abstract landscapes using just a couple of watercolor techniques—wet-in-wet gradients and dry brush, with some scraping and scratching. I had a lot of fun with those and kept a bunch.

|

| I painted this one for a specific poem. A bit like being a kids' book illustrator. |

Mirror, mirror … never mind

This year I tried something new: painting postcards specifically for the poems, and also the reverse—writing ekphrastic poems about my own paintings on the postcards*. I sort of liked painting to complement the poems; that was a free-wheeling exercise in abstraction, or in surreal representation. But I didn’t like writing ekphrastic poems about the paintings; that felt weirdly self-referential, a kind of narcissistic loop. Like, I painted this somewhat abstract landscape, and now I’m writing a poem about it. It was a sham, a trick I was pulling on the reader—a made-up poem about a made-up visual scene. It was like trying to build a house on air. There didn’t seem to be much point to it.

One of my favorite poems of the month was about a baby that someone at a party asked me to keep an eye on for a few minutes. We were outside, it was raining a bit, the baby was sleeping in a little covered hammock—and suddenly the world exploded into metaphors. That was way better than any made-up landscape. There’s something to be said for writing poems about real things. This was a good reminder of that.

* Coincidentally, I just did a (live! in-person!) reading here in Ashland with my friend Allan Peterson, a renowned poet and longtime visual artist and art professor. During the Q&A after our reading, he said that he has no desire to pair up his poetry and artwork—say, in a book of his poems and paintings—because then the writing and painting “will be trying to explain each other.”

Recently Allan asked how my art was coming along, and I said I’d become so engrossed in painting small postcards that I hadn’t painted much of anything else recently. He said he once had a student who felt she’d confined herself too much by always making small paintings, and he advised her to “use bigger brushes.”